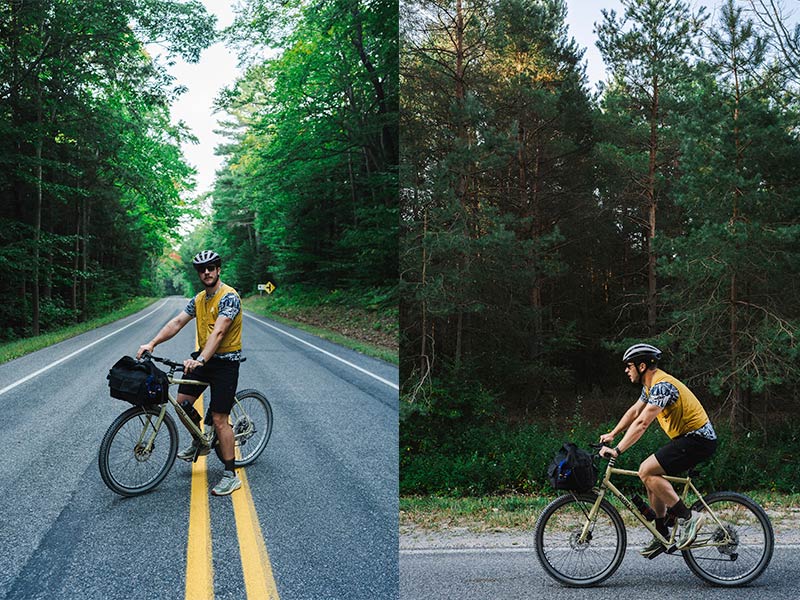

Matt Medendorp shares his midwestern musings on steel-frame bikes, towing a canoe with human power, and avoiding the easy way in life.

Out of Office, Into Water

The canoe slaps against my back tire, making a grinding sound and emitting a rubber-burning stench that isn’t good for my bike tire and certainly not good for a canoe we plan to paddle to dinner tonight. Boats work best when they remain watertight (so I’m told). Our group of three pauses for what seems like the twelfth time. Less than a quarter mile from our cedar shack cabin, we’ve struggled to dial in the correct canoe-to-bike distance to wrangle our 17.5-foot Old Town to the mouth of the Crystal River. Liam, our photographer and native son of Leelanu’s Peninsula, has his mental maps up and running, calculating the distance to our put-in and time until golden hour. Kurt, my childhood best friend and expert knot tier, is putting his Eagle Scout skills to the test with a length of paracord and a lighter, rigging our canoe trailer. Then there’s me: part-time writer, full-time schemer whose idea landed us in this predicament.

We’re up in Northern Michigan for 72 hours of human-powered adventure in the Mitten state’s crystal lakes and trout-filled rivers. Human, powered, but still technology adjacent—we’re more Thoreau at Walden than an unfilmed Naked and Afraid. Charity and visitors greatly encouraged, the human-powered aspect meant to shake up our modern routine, not perpetuate a false sense of rugged individualism. I’d love to be a luddite, but I’m not. I’m ingrained in a digital existence. I’d like to rebel, but I can’t seem to get off the pixelated hamster wheel. So, like rehab, it may be time for something drastic. I’m not a fan of half measures. Biking eleven miles feels like a waste of time, biking one hundred and eleven miles feels like a great way to spend a Saturday. Sobriety or binge drinking, either works. Let’s toss moderation out the window, and caution while we’re at it. Hence, the elimination of the easy way. Also, there’s always a good excuse to have some fun on bikes.

Pulling this canoe, however, is not fun. It’s stupid. At least until we dial in the correct amount of slack, circumventing the designed system with a complicated spider’s web of paracord checks and balances. Then, towing a canoe behind a bike is turning out to be not dissimilar to biking with toddlers— we have to stop constantly, there are unexpected noises, and I’m at the mercy of my own misguided decisions that greatly preceded the activity in question. The bike is more than up to the task: A steel-frame Surly Bridge club in a luxurious Whipped Butter colorway, all the better companion to the morel stickers decorating the downtube. The canoe cart leaves a little bit to be desired—the dredges of the internet have turned up a Canadian Dragon’s Den (our northern neighbor's off-brand shark tank) veteran of a start-up. In fairness, I ordered the wrong size for my rather large canoe in the rush of last-minute trip prep. At the very least, the boat already has enough dents in it. But that’s the beauty of a weekend like this, a balance of the planned and unplanned.

The Planned

Includes biking-towing a canoe to a put-in on the gently flowing Crystal River, paddling to dinner at the farm-to-table Mill, bike towing our canoe bike to our cabin basecamp in order to jumpstart our long weekend of human-powered adventures, exploring the food and the landscape of Northern Michigan. Pairing bikes, water adventures, and good food: oysters (imported) and beer basted brats (native), slow ascents up glacial formed hills, eye-watering descent down the same. Sail boats and surfboards, single track and rutted dirt roads. Rinse and repeat, until the responsibility of jobs and families beckons us back to reality.

The Unplanned

An unexpected river crossing, light trespassing, heavy chafing (wet waxed cotton pants may not have been the optimal dinner attire), cocktail hangovers, flat (unsurfable) lakes, a couple of hitched rides, cheap afternoon beers, spontaneous renditions of Gordon Lightfoot’s Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald. Hot sand on your feet, cold lake water on your skin, the tingle of it all drying off on a leisurely bike ride away from the dunes.

There’s a wonderful perspective that accompanies trips like this. On an average day, the unplanned diversion upends my psychological equilibrium. A toddler that can’t find his shoes makes you late for gymnastics, means I miss a work call, means I can’t hit my word count for the days and the endless cascading of deadlines and frustrating that result. On a trip like this, you anticipate hiccups. A malfunctioning bike trailer means roadside repairs, means you miss golden hour at the restaurant but that you stay late at the restaurant, stash your canoe in the reeds, bushwhack back to your bikes, and use two headlamps between three people to cut the deep darkness, indigenous to places with less people. You stay flexible, you get creative, and you find solutions. The unplanned is where the magic happens, where the real stories come from.

It pays to shake the dust. Imaginary situations train us for the real deal. Life is no guaranteed picnic. We each have a different way of dealing with it. Lately, I’ve been attempting to chase a nobler distraction. Skip the easy dopamine of an Instagram reel, move the needle from consumption to use.

Years ago...

I worked on the tangential margins of an outdoor adventure film. The U.S. men’s national rafting team was attempting to break the speed record of the Grand Canyon. They built a boat out of fiberglass and rubber, a great spider of a thing that they planned to row—rather than paddle—down all 277 miles of the Grand Canyon's Colorado River, with the goal of beating 34 hours and 2 minutes.

The team’s captain said something that stuck with me, something that was the crux of modern-day adventuring, a bedrock of philosophy that’s anchored future wanderings for me. It was about the philosophy of insignificance. They were not going to change the canyon; the canyon would change them. That the river doesn’t care if anyone is on it — its course is not affected by a few guys on a raft trying to go fast. Nor is it a real hardship to put yourself in voluntary situations where things are difficult, where you leave modern convenience behind for a few days. But it is practice for when times get tough. We’re not going to change the canyon, but ideally the canyon does something to change us.

That’s the beauty of a steel frame bike like the Bridge Club—it’s neither dirtbag minimalism nor optimized tech future. It can rip, but it takes some work to pedal the steel beast up a one-mile ascent. It’s both easy and hard, adaptable if you have the will and work ethic to try.

The Bridge Between Easy and Hard is Made of Steel

I write a lot about stuff. Modern journalism (if we can call commerce-based writing that) predicates a profit system based on a complicated web of affiliate links, percentages, and every expensive recommendation. I’ve ridden very nice bikes and some not very nice bikes. I borrow a life of excess and then return it. That’s the beauty of a steel frame bike like the Bridge Club— it’s neither dirtbag minimalism nor optimized tech future. It can rip, but it takes some work to pedal the steel beast up a one-mile ascent. It’s both easy and hard, adaptable if you have the will and work ethic to try.

Doing things the easy way is easy. And there’s a place for that. Humans are drawn to the lowest common denominator as a matter of genetic survival: high calorie food, saturated in fat, salt and sugar. Combustion engines. Those little electric chairs the cartoon people in WALL-E use in place of ambulatory function. A genetic code drives us to take an easier path, more accustomed to a time when calories were scarce, and beds made of damp leaves. Obviously, that’s no longer our reality. Bad food is cheaper than good food. Our screen time rockets up while our attention spans diminish.

On our final afternoon, my friends were sleeping. Our morning excursion on the sailboat, the parade of cheap beer and the good lunch after at Farm Club had lulled the group to an afternoon respite. But the Bridge Club—and the adjacent single track— called to me. Sure, the steel frame had tug-biked a canoe to an eventful launch, had set the pace on sustained glacial hills, and had come out all the stronger for it. But it had yet to eat up some of the exact terrain the big tires called for. So, I skipped the nap, stripped the bike of its bikepacking accouterments and nosed it out the driveway to the sandy bluffs.

Good Plain Fun

This was biking like a kid, setting up plywood jumps over drainage ditches and tumbling again and again into cool spring grasses. Instead of plywood there were rock gardens, punchy climbs, flowy downhills. Rinse and repeat.

On my last lap, I heard the spin of an accompanying chain and slowed my downhill speed as I fishtailed around the corner. A fellow mountain biker, well into his 70s and kitted out with full downhill gear piloted a full suspension towards me. We exchanged a few quick smiles. “Great day for this, huh?” I said. “Nothing better,” he grinned back, pedaling uphill.

Words: Matt Medendorp

Photos: Liam Kaiser

Surly Bikes

Surly Bikes